How the Cook County Assessor Failed Taxpayers

Joseph Berrios’ error-ridden commercial and industrial assessments punish property owners, benefit lawyers

AMID THE MOST TUMULTUOUS real estate market since the Great Depression, Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios produced valuations for thousands of commercial and industrial properties in Chicago that did not change from one reassessment to the next, not even by a single dollar.

That fact, one finding in an unprecedented ProPublica Illinois-Chicago Tribune analysis of tens of thousands of property records, points to a conclusion that experts say defies any logical explanation except one:

Berrios failed at one of his most important responsibilities — estimating the value of commercial and industrial properties.

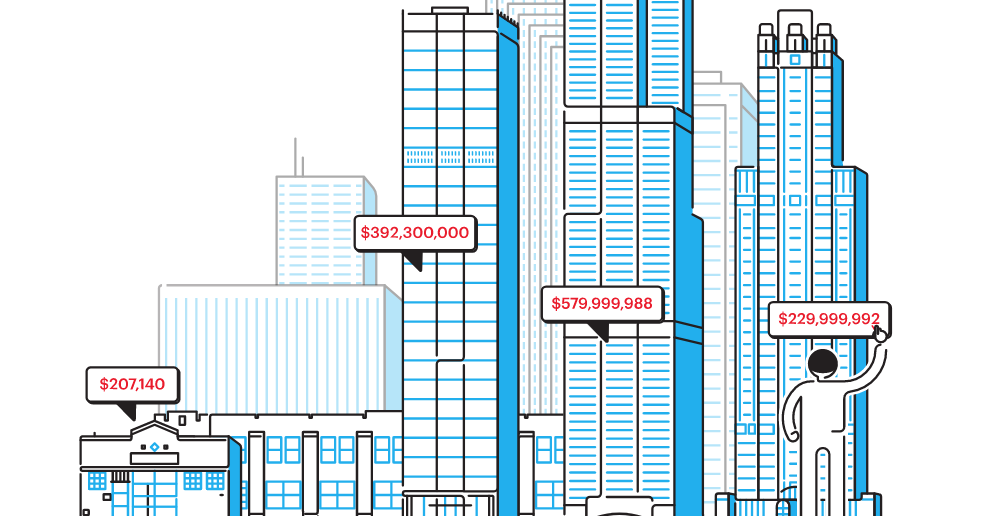

What’s more, a separate analysis reveals commercial and industrial property assessments throughout Cook County were so riddled with errors that they created deep inequities, punishing small businesses while cutting a break to owners of high-value properties and helping fuel a cottage industry of politically powerful tax attorneys.

And because commercial and industrial properties as a group were not assessed properly, residential homeowners across the county were forced to carry an additional and unnecessary burden, paying more in property taxes than they would have otherwise.

State law says the assessor must revalue property every three years. Yet Berrios, using methods hidden from the public, repeatedly produced initial valuations of commercial and industrial properties — known as first-pass values — that did not change.

For example, as the financial crisis cratered the real estate market in 2009, Berrios’ predecessor estimated the value of a stout brick building in a bustling commercial area on Chicago’s Northwest Side at $13,455,132.

Three years later, in 2012, Berrios had taken office and the commercial real estate market had come roaring back. Yet the assessor’s estimate did not change: $13,455,132.

In 2015, as the market continued to climb, Berrios’ office once again arrived at the same number: $13,455,132.

Three straight reassessments. Three identical values.

Given the complexity of the commercial real estate market and its dynamic nature, experts say it is inconceivable for such values to remain the same over time.

But an analysis of more than 40,000 parcels of commercial and industrial property in Chicago shows that, under Berrios, more than two-thirds had identical first-pass values in at least two consecutive reassessments.

Nearly a fourth of the parcels — pieces of real estate that receive their own assessment and tax bill — had the same initial value for the Chicago reassessments of 2009, 2012 and 2015.

Under Berrios’ predecessor, James Houlihan, just 1 percent of parcels saw no change over two or more reassessments conducted in 2003, 2006 and 2009.

“For values to stay exactly the same, that indicates they aren’t doing anything,” said Peter Davis, an expert on assessments who helped write standards for the International Association of Assessing Officers, a professional organization that develops guidelines used around the world.

“If your models are working correctly, the chances of values staying exactly the same are virtually impossible.”

Berrios already is under fire for producing inaccurate residential assessments that burdened poorer homeowners, problems the Tribune’s series “The Tax Divide” uncovered in June. Berrios, who is up for re-election next year, testified before the county board about his methods in July, and Board President Toni Preckwinkle ordered a study of residential assessments.